The word “yoga” comes from Sanskrit and goes back to the root word yuj.

The root word yuj means on the one hand “to bring two things together”, “to unite” and on the other “to focus the mind”. As can be seen from the first definition, yoga strives to integrate all aspects of the personality. This includes body, mind and soul. All these aspects are interrelated and interact with each other. Yoga attempts to create a harmonious balance between these aspects and to bring about a feeling of wholeness. Furthermore, yoga can be understood as a science of the mind, whose exercises are tools to clear, transform and change the mind.

“…true yoga was always aimed at recognizing us as that which is eternal, infinite, and unchangeable.”

Gregor Maehle

The yoga practiced today differs from traditional yoga primarily in terms of the motivation of the practitioners. The original motive was of a mental and spiritual nature, which encompasses the pursuit of complete mental alertness, whereas today the interest in yoga is primarily focused on stress management, reducing ailments and promoting health.

Ashtanga Yoga

The eight-limbed yoga path according to Patanjali

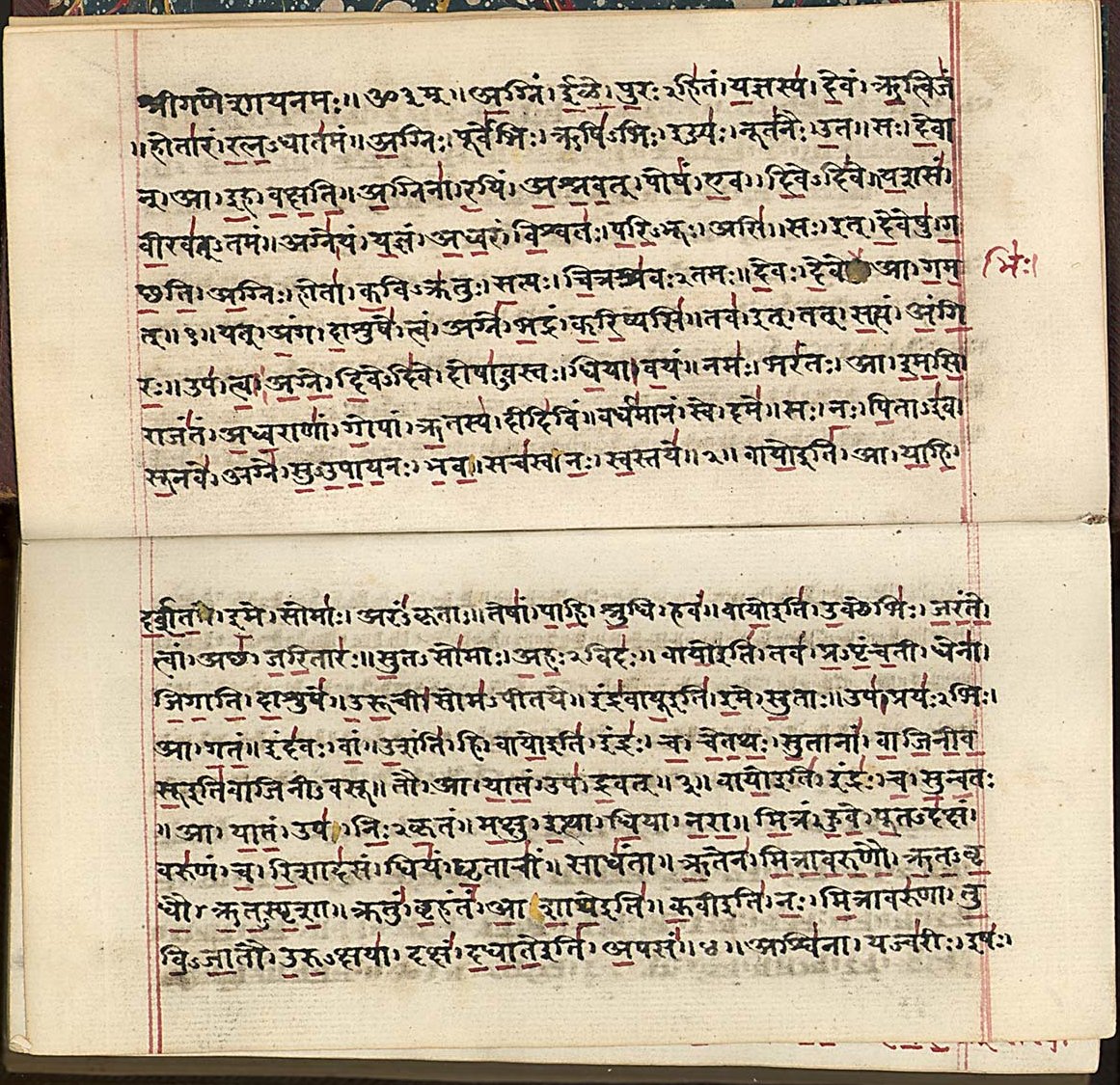

Translated from Sanskrit, “ashta” means eight and “anga” means limb. Ashtanga yoga can therefore be understood as the eight-limbed yoga path. Ashtanga yoga was described by the Indian scholar Patanjali in the second part of the Yoga Sutras text. This text, based on 195 Sanskrit verses, is divided into four parts and can be understood as a guide to yoga. The 195 yoga sutras explain the central concepts and the methods to achieve the goal of yoga, the realization of the self by calming the mind.

“Yogas citta vritti nirodah.”

Sutra 1.2

Patanjali emphasizes two central concepts, which are the main means of achieving the goal of yoga: Abhyasa means regular yoga practice and Vairaghya implies the cultivation of inner detachment or detachment.

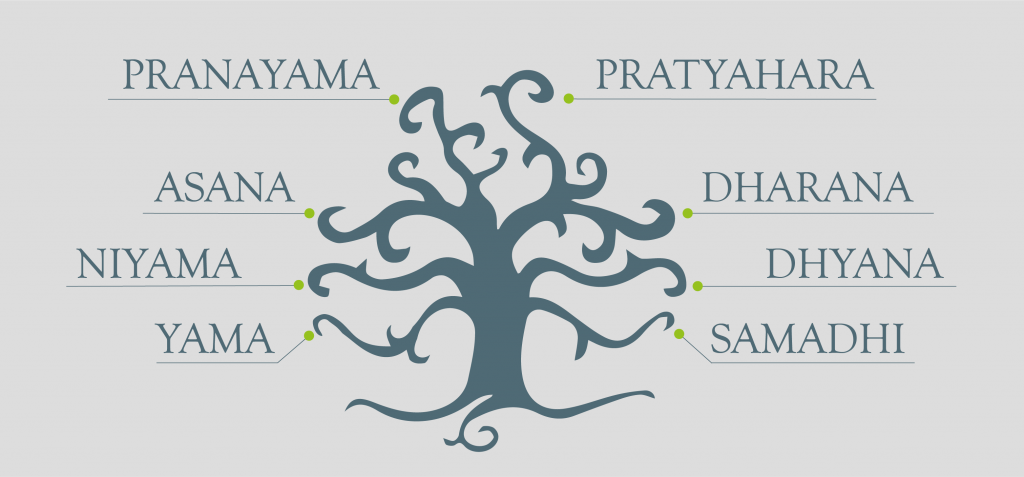

The eight limbs of Ashtanga yoga

The eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga include Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi.

Yama is divided into five moral principles that indicate how individuals should interact with other people, living beings and the environment so that they can lead a fulfilled and harmonious life. These include: Ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (truthfulness), Asteya (non-stealing), Brahmacharya (moderation) and Aparigraha (non-possessiveness).

The five niyamas (personal conduct) focus on the attainment of contentment(santosha), inner and outer purity(sauca), discipline(tapas), theoretical and practical self-study(svadhyaya) and spiritual unfoldment(isvara pranidhana).

The third limb includes asana (postures). By practicing specific postures, the practitioner is able to build stamina, strength, flexibility and steadiness of mind. If it is possible to sit for a certain period of time without feeling any discomfort, the practitioner can begin practicing the fourth limb, Pranayama (lengthening the breath) and the fifth limb, Pratyahara (withdrawing the senses to increase inner awareness). Pratyahara represents a special position among the eight limbs in that it builds a bridge between the outer world and the inner world. Through pratyahara we begin to direct our senses inwards, for example by observing our breath. In an attempt to focus our concentration on a point, on an object, we start practicing meditation. Only when we are able to direct our perception inwards despite the thoughts, sensations and sounds that arise can we achieve a deep state of concentration, the different intensities of which are described in the limbs Dharana (concentration), Dhyana (meditation) and Samadhi (bliss).

The combination of the fifth, sixth and seventh limbs(Pratyahara, Dharana and Dhyana) brings about a state of deep meditation in which thoughts cease to exist. The culmination of all eight limbs is the attainment of samadhi, complete spiritual alertness, the highest, divine counter-value, the absolute highest consciousness.

Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga

In the literature, Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga is often also referred to as Ashtanga Yoga and it seems as if the name similarity with Patanjali’s Ashtanga Yoga was chosen deliberately. Gregor Maehle writes in this regard:

“I asked the Ashtanga master K. Pattabhi Jois about the Vinyasa method: ‘This is Patanjali Yoga’ he pointed out … Yoga Sutra and the vinyasa method are really only two sides of the same coin”.

In Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga – a dynamic and physically intensive Hatha yoga style – selected asanas are combined into six fixed series of exercises that build on each other and differ in terms of the strength, flexibility and endurance required. The special thing about this yoga style is the synchronization of breath and movement, whereby the breath harmoniously initiates the entry into an asana and the exit from the asana. This flowing connection of the individual postures into a whole makes it possible to experience meditation in motion and, with regular practice, allows us to experience a state of deep concentration and timelessness.

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya is considered the most important teacher of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga. One of his most important and long-standing students was Sri. K. Pattabhi Joiswho opened Ashtanga Yoga to Western students and passed on the teachings of this system with tireless dedication until his death (May 2009) at the Ashtanga Yoga Institute (KPJAYI) in the South Indian city of Mysore. His daughter Saraswathi, his son Manju and his longtime student and grandson Sharath carry on the Ashtanga tradition in the next generation with great dedication.

Key features of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga

The basic principle of Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga practice consists of the combined application of deep and constant Ujjayi breathing, muscular body locks(bandhas), the calm alignment of the gaze(drishti) and the combination of breath and movement in Vinyasa. The combination of the first three techniques mentioned is called Yoga Tristana.

Ujjayi

The powerful Ujjayi (victorious breathing) is done through the nose and generates heat in the body. By narrowing the glottis, inhalation and exhalation are controlled, deliberately slowed down and lengthened. The air friction creates a gentle hissing sound in the throat. The friction is subtle, gentle, without causing scratching.

Bandhas

Bandhas are muscular energy locks. They ensure that energy can be compressed and retained in the body. A distinction is made between three bandhas: mula, uddiyana and jalandhara bandha. Jalandhara Bandha (chin lock) is performed during Kumbhaka, the breathing pause in Pranayama, and is only rarely used in a weakened form in Ashtanga Vinysa Yoga. The approach of Uddiyana Bandha (“soaring lock”) and Mula Bandha (root lock), on the other hand, are consciously activated in every asana. The subtle contraction of these muscle groups stabilizes the lower back, helps to build strength, provides the necessary body tension and body control so that even challenging exercises can be mastered and conveys a feeling of lightness when practising.

Drishtis

Drishtis are so-called points of gaze or concentration. They refer to the direction in which the practitioner looks during each posture. A total of nine different drishtis are distinguished: Nasagrai (tip of the nose), Broomadhya (between the eyebrows), Nabi Chakra (navel), Hastagrai (hand), Padhayoragrai (toes), Parshva (right or left side), Angushta Ma Dyai (thumb) and Urdvha (upwards). Drishtis help the practitioner to direct their attention inwards in each asana and not to wander off with their eyes or thoughts. They also help to maintain concentration and balance.

Vinyasa concept

On the one hand, vinyasa refers to breath-synchronized movement sequences that connect the individual postures with each other. The term vinyasa is derived from the Sanskrit word “nyasa” and the prefix “vi”. The Sanskrit word “nyasa” means “to place” and the prefix “vi” means “in a special way”. In this sense, the movements of the body are adapted to the movements of the breath in a “special way”.

“Oh yogi, don’t practice asana without vinyasa.”

Rishi Vamana

The Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga series

Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga is structured in series. Each series consists of a fixed sequence of asanas and has its own focus. In the Primary Series, called Yoga Chikitsa (yoga therapy), the focus is on forward bends, hip-opening exercises and vinyasas. The focus is on detoxification, building strength and flexibility and correct body alignment. The Intermediate Series, also known as Nadi Shodhana (cleansing the nadis/nerves), goes one level deeper and has a stronger influence on the nervous system through a variety of backbends. This strengthens the spine and increases its flexibility. The Advanced Series A, B, C, D(Sthira Bhagah Samapta) require an even higher degree of flexibility, strength and humility.

Traditionally, the practitioner begins with the asanas of the Primary Series, which forms the basis for all further series. Once the student has learned the postures of the first series, the teacher will add individual asanas from the Intermediate Series. When the student has understood the intention of these asanas and has built up sufficient strength, stamina and inner strength, they are ready to practise the Intermediate Series on their own. This process is repeated for all other series.

Yoga & Health

In ancient Indian scriptures such as the Upanishads, the epic Bhagavadgita or the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, health is a central theme. Health is presented as an effect of yoga practice and at the same time understood as a process variable.

The understanding of health in yoga thus corresponds to today’s process-oriented view of health, in which health is seen as a process in the continuum between well-being (health) and discomfort (illness) (cf. the concept of salutogenesis by A. Antonovsky).

According to Indian thought, the transience of human existence and the realization of temporality is the cause of suffering-causing entanglements with the world. Called kleshas and antarayas according to Patanjali, these are specific behaviors that, while corresponding to the nature of the mind, can lead to unconscious tensions and manifest in psychosomatic disorders and disease. The yoga methods (yama, niyama, asana, pranayama and meditation) were developed to counteract precisely these imbalances, to recognize and master them.

Effect of yoga

A regular yoga practice (which includes physical exercises, breathing exercises, cleansing techniques, forms of mediation and ethical behavior (Ashtanga Yoga) leads to physical strength and emotional resilience.

- Yoga reduces stress and increases stress resistance,

- leads to a more relaxed attitude and a positive self-image,

- helps to change evaluation patterns,

- helps to uncover negative social structures and

- reduces tolerance to harmful living conditions and behavior.

- Yoga offers regular exercise and relaxation,

- leads to a conscious, responsible and moderate lifestyle, a desire for a healthy diet and moderate consumption of luxury foods.

The vitality you feel after practicing yoga makes you experience health as improved well-being.

Yoga history

A historical overview of yoga is best obtained by considering Indian philosophy, as yoga is deeply rooted in Indian culture and tradition.